Antique timepiece expert, Andrew Crisfold, shares how Breguet’s innovations and marketing prowess were truly ahead of his time.

By Mr Shamim Quadir (Senior Communications Officer), Published

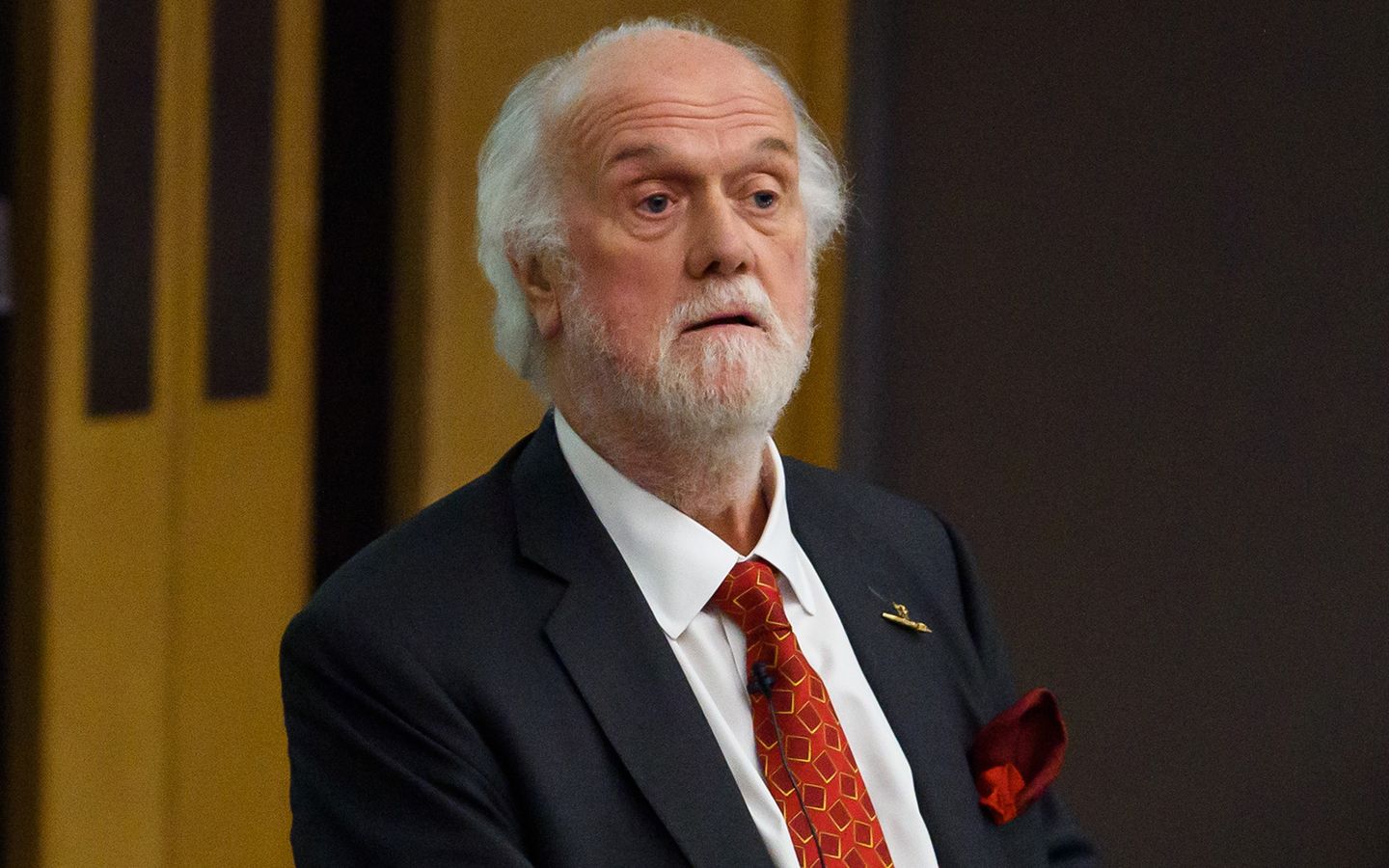

On Wednesday 29 November, the School of Science & Technology welcomed Andrew Crisfold to deliver its annual George Daniels Lecture at City, University of London. In 1973, Andrew founded Bobinet Ltd., a company specialising in antique clocks, watches and scientific instruments, and which now offers clients worldwide advice on clocks and watches from the 16th to the 20th centuries.

The lecture was introduced by City President, Professor Sir Anthony Finkelstein, and Kenneth Grattan, George Daniels Professor of Scientific Instrumentation at the School.

A horologist is a maker of clocks or watches. Professor Finkelstein spoke about the extraordinary life of British Master horologist, Dr George Daniels, an alumnus of the Northampton Institute, City’s predecessor institution, and in whose honour the George Daniels Lectures have been held since 2013. He reminded the audience of how Daniels’ interest in things mechanical was not solely confined to his expertise and artistry in watchmaking, but also in his collection of vintage automobiles. Both are areas which fascinate the President (as an engineer himself) and who added in his Introduction how very much he was looking forward to the upcoming lecture.

The original tick-tock influencer

Andrew Crisfold delivered the lecture on one of his speciality areas, the work of Abraham-Louis Breguet, a Prussian horologist who became the indispensable watchmaker to the scientific, military, financial and diplomatic elites of Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

He began his lecture by providing some fascinating insights into the watchmaking innovations and marketing prowess which made Breguet truly ahead of his time.

These insights spanned practices which are widely accepted as marketing conventions today, including:

- having an instantly identifiable product

- a prestigious point-of-sale

- excellent promotion and advertising

- celebrity endorsement

- production of publicity pieces

- personalisation of the product

- novel purchasing arrangements and

- accessorising and distinctive packaging.

Pocket watches of Breguet’s time were notorious for their fragility, due to their delicate and finely balanced mechanisms. Andrew discussed Breguet’s revolutionary innovation of the ‘pare-chute’ shock protection system, which he trialled in 1790 and by 1792 was used on many of his watches. Breguet observed that the pivots of the balance wheel (which keeps the watch’s time) were the most vulnerable part of the watch, so gave the pivots a cone-in-dish shape, and attached them to a spring. This new system made Breguet’s watches significantly less fragile, which only enhanced their reputation further.

Breguet also sought to capture the imaginations of his customers through the ‘super complication’ of his timepieces. In horology, a ‘complication’ is any function of a watch that goes beyond its primary function of telling the time, such as showing the date, or the day of the week. Andrew shared how Breguet’s watches went from a staggering 33 complications in some models up to a mind boggling 57 complications for one model.

Andrew remarked on how now, as then, customers do not want to spend money on an unidentifiable watch, using the Rolex and Tag Heuer brands as examples of timepieces with iconic status today. He showed examples of Breguet watches with characteristic design features that made them instantly identifiable as his work to his contemporaries.

He shared an example of how Breguet’s marketing acumen helped him bypass a social more of the time to enable him to raise the profile of his products. In the French society of that time, it was deemed impolite to look at one’s watch when in company. Breguet employed the use of a characteristic key and link that would be worn at the buttonhole end of the watch’s chain to show one was wearing a Breguet without the need to remove it from one’s pocket.

In another example relating to the personalisation of Breguet timepieces, he shared how for one wristwatch model a customer could have a single hole punched in the strap upon its purchase and fitting at Breguet’s store. At the same time, this dealt away with the necessity of any packaging – ironically an area in which Breguet also excelled in marketing.

Notable customers and in popular fiction

Andrew shared how a Breguet watch was famously commissioned for Queen Marie-Antoinette of France (watch no. 160), but was not completed until after her execution during the French Revolution in 1793, and indeed, was only completed by Breguet’s workshop four years after his own death.

In what became a somewhat infamous commission, he also described how Joseph Bonaparte commissioned a Breguet watch for himself - with a map of Spain enamelled on its back - to commemorate being appointed as King of Spain in 1808 by his brother, and French Emperor at the time, Napoleon Bonaparte. However, Joseph then lost the throne of Spain and refused to purchase the watch. In an ironic twist, the watch was instead bought by the Duke of Wellington upon his arrival in Paris after victory at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Staff, students and guests at the George Daniels Lecture: Abraham Louis Breguet, the original tick-tock influencer

Andrew discussed how the Breguet watch became celebrated in the popular culture of the time through being referenced in the works of famed novelists such as Alexandre Dumas and Jules Verne. The latter’s character, Phineas Fogg, took a Breguet with him when he set out to go around the world in 80 days.

He noted how novelist, Stendal, favourably compared the reliability of Breguet’s work with that of the human frame, in his travel piece Rome, Naples et Florence, published in 1817:

Andrew also shared how a selection of over 20 of Breguet’s contemporary timepieces recently went on display for the first time at the Science Museum (until 8 September 2024), and encouraged his audience to pay the exhibition a visit.

Following his lecture, Andrew deftly fielded a wide array of often niche questions from the horologists and other interested parties who had travelled from far and wide to learn about Breguet from him, including:

Did anyone master Breguet’s signature used on his timepieces? You would need the master die, which George Daniels did have, and having restored Breguets, could use a pantograph to put the signature back on.

How many Breguets were made? By the time of his death in 1823, the numbering system was around 3,000. By the 1850s the number was up to 5,000 and then a new series was started.

Were there guarantees and aftersales service? There are no contracts or bills of sale that mention guarantees, but Breguet made his watches to work. Lots of customers were dispersed to far flung areas of Europe. He did have his team, so a watch would likely have been able to have been mended.

Reflecting on the event, organiser, Professor Grattan said:

Find out more

Visit the exhibition until Sunday 8 September 2024: Abraham-Louis Breguet: The English Connection - Clockmakers’ Museum, Science Museum London.