Dr Dominic Davies publishes new book The Broken Promise of Infrastructure, which investigates the cultural politics of infrastructure in Britain.

By Eve Lacroix (Senior Communications Officer), Published

“In recent years, I noticed policy catchphrases like levelling up being used to invoke the greatness of infrastructure in Britain, even as very little new infrastructure is actually getting built,” said Dr Dominic Davies, Senior Lecturer in English Literature at City, University of London.

Dom’s new book The Broken Promise of Infrastructure, which was published by Lawrence & Wishart in late 2023, investigates this gap.

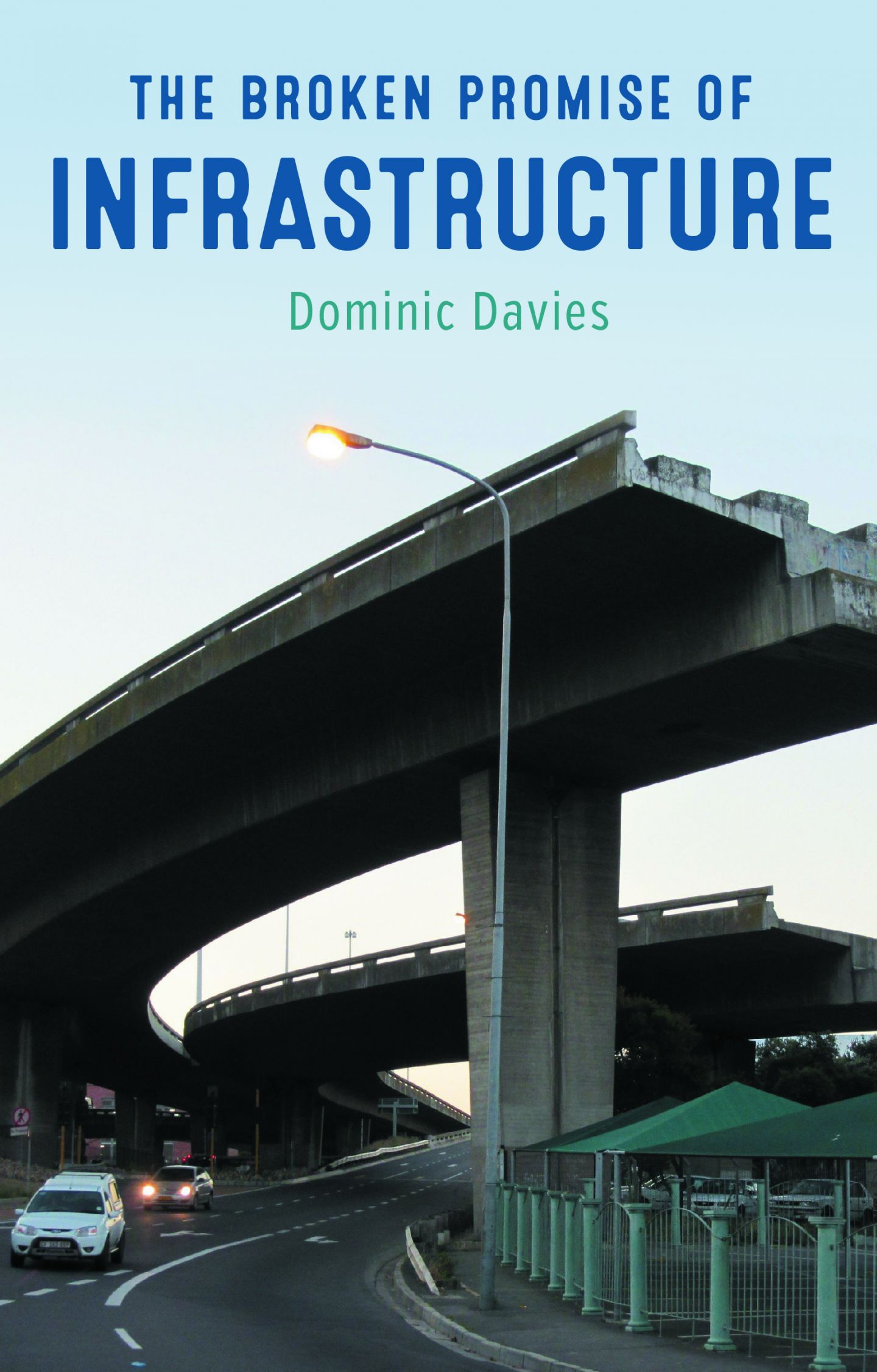

Infrastructure failures in the UK have dominated the news in recent years. From the RAAC scandal stopping primary schools from opening in September 2023, to the lingering effects of asbestos in hospitals, to the 2017 Grenfell Tower tragedy, there has been chronic and often deliberate underinvestment in British infrastructure.

One example of infrastructure that Dom frequently noticed being used as a symbol is the railway. According to Dom, an overreliance on nostalgia for past infrastructure may be holding Britain back.

“We are hugely nostalgic for the railways in Britain as a symbol of lost imperial greatness,” he said. “I wanted to explore this central contradiction between the economic reality of infrastructures and the way they are imagined in culture and politics.”

While the building of railways in former British colonies is frequently billed as one of the “gifts” the British empire offered its colonies, in reality they were used to extract coal and cotton, to funnel wealth to the metropolitan centre, and to deepen global inequalities.

The symbolism of the railway remains powerful: today, the cancellation of large sections of HS2 project reveal the UK to be lagging behind its European peers in developing high speed railway networks.

Through The Broken Promise of Infrastructure, Dom poses a question to his readers: what if we designed infrastructures to stay put in a place, rather than building them to escape somewhere else?

“The infrastructures we build are often centred on ideas and feelings of mobility – of the ability to get away from places,” Dom said. “What would infrastructure look like if it was designed to facilitate feelings of belonging instead?”

He argues that Britain’s failing public transport networks force people into car use, amplifying traffic congestion and alienating people from one another as well as the places they drive through.

“We still need new roads and plenty more buses and railways, but these would need to be publicly owned and built so they circle wealth back into the communities they are supposed to serve, strengthening a sense of place in the process,” he said.

He believes that infrastructures, and particular the way we write, think about, and imagine them, have the ability to revolutionise the UK’s physical geography and to make the most of its strong regional identities.

Discussing his book, Dom said:

Dom is also the Programme Director for the University’s BA English degree, a role which connects with his research interests.

“English students have the skills to see these how these stories shape our world just as concretely as infrastructure,” he said. “By telling new stories, we can begin to design infrastructure differently in the future.”