Dr Dominic Davies, Senior Lecturer in English, writes on how graphic narrative has proved to be particularly adept at highlighting climate issues

By City Press Office (City Press Office), Published

As the scale and severity of the environmental crisis escalates, our shelves and screens have been bombarded by a whirlwind of climate-themed genres, from climate fiction (cli-fi) to disaster movies.

These books and films tend to stumble on the same problem: how to connect the day-to-day experiences of human life to the far greater scales of environmental change? And more importantly, how to do so in a way that does not collapse into hilarious absurdity or futile apocalypse, but that makes the crisis feel immediate and real?

In the last few years, the environmental concerns turning up in fiction and film have found expression in comics as well. But there is something special about the form of “graphic novels” or “graphic narrative”.

Because it combines image and text, laying them out together on the page, graphic narrative has proved to be particularly adept at bridging the macro scales of environmental change with the micro scales of our everyday human lives.

1. Here by Richard McGuire (2014)

As its title suggests, Here is a graphic novel that is set in a single place: the living room of the author’s childhood home. In distinct contrast to the flying cameras of disaster films, our perspective on this space never moves. Spatially, the graphic novel remains rooted to the familiar human scale of a normal front room.

However, while this space never changes, McGuire uses timestamps and floating panels to show images of the same place as it has changed through billions of years.

We are shown familiar human experiences, from births and deaths to parties and games. But McGuire also presents us with scenes of this patch of earth when it was a hostile gaseous ball, long before the evolution of Homo sapiens, and he zooms us forward by tens of thousands of years, allowing us to glimpse a future after humans.

'Here', by Richard McGuire. (Penguin Random House)

While this graphic novel remains centred on the human, it also encompasses the inconceivable durations of time that make up planetary change. Because their form requires them to stick mostly to a linear sequence of cause and effect, novels and films are unable to capture this clash without becoming incoherent.

The spatial arrangement of graphic narrative, however, allows McGuire’s novel to juxtapose vastly different scales, which reveals their connections. Here is able to show rising sea levels zooming back from the future and crashing through the windows of homes that are heated with fossil fuels.

2. Paying the Land by Joe Sacco (2020)

Joe Sacco’s documentary comic, Paying the Land, approaches the same problem in a different way. It tells the story of the fossil fuel industry in Canada’s Northwest Territories and its violent consequences for the Indigenous Dene communities who have inhabited the land for thousands of years.

The title comes from the ancient Dene practice of repaying the land with a gift each time they take something from it that they need to survive, like wood, fish and caribou. By contrast, fracking companies retrieve oil and natural gas from far below the surface by injecting dangerous cocktails of chemicals into its substrates. Rather than showing respect for the land, they pay it back with poisonous toxins.

Sacco illustrates these two different relationships to the land in the layout of his pages. When we are with the Dene, who live sustainably on the land, there are no lines or grids separating us from the environment depicted in the book’s images. But when the comic turns to the fossil fuel industry, these straight lines and sharp grids break up both the page and the land, much like the toxins blasted into it during the fracking process.

The graphic novel’s visual form therefore trains us in different ways of seeing the land: we can parcel it up into property and resources, or we can recognise that we are living in the very same environment that is being poisoned.

By showing the connections across geographic and historical scales that are usually invisible to us, Paying the Land reveals that the violence and displacement experienced by the Dene is intimately linked to the fuel that powers our cars and heats our homes.

3. Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton (2022)

Recounting her autobiographical experience as a labourer on the Alberta oil sands, Kate Beaton’s graphic memoir, Ducks, shows how resource extraction has serious consequences for young Canadians.

'Ducks' book jacket, by Jonathan Cape

Burdened with student debt, Kate is driven to find work in the extraction industry. Working on remote mining sites that lack sufficient managerial oversight, she finds herself at risk of male violence. Though struggling with this toxic culture, the combination of her personal financial pressures with a failing economy built around fossil fuels prevent her from leaving before her loan is paid off.

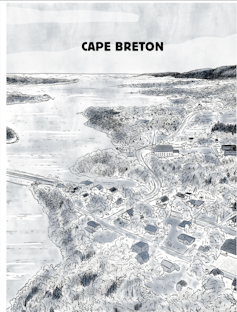

Cape Breton page from 'Ducks', by Jonathan Cape

Beaton’s chapters begin with eerie drawings of the oil sands that look like strange lunar landscapes. The isolation and claustrophobia of these settings is then communicated through small panels that make up the rest of the comic.

Ducks affords an unusual view of the structural pressures that impact violently upon people’s everyday lives, but especially those of women and young people.

Comics are distinct from films and novels in their depictions of the climate crisis. In juxtaposing images on the page, they encourage readers to draw connections that show how the sometimes incomprehensible scales of environmental change are bound up with the most intimate details of our everyday lives.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.