Miguel-Ricardo Nkegbe, researching for his PhD in The City Law School, explores the possibilities for reducing space junk.

By Mr John Stevenson (Senior Communications Officer), Published

Miguel-Ricardo Nkegbe has taken a keen interest in debris.

Not just any debris, but space debris, which is also known as space junk.

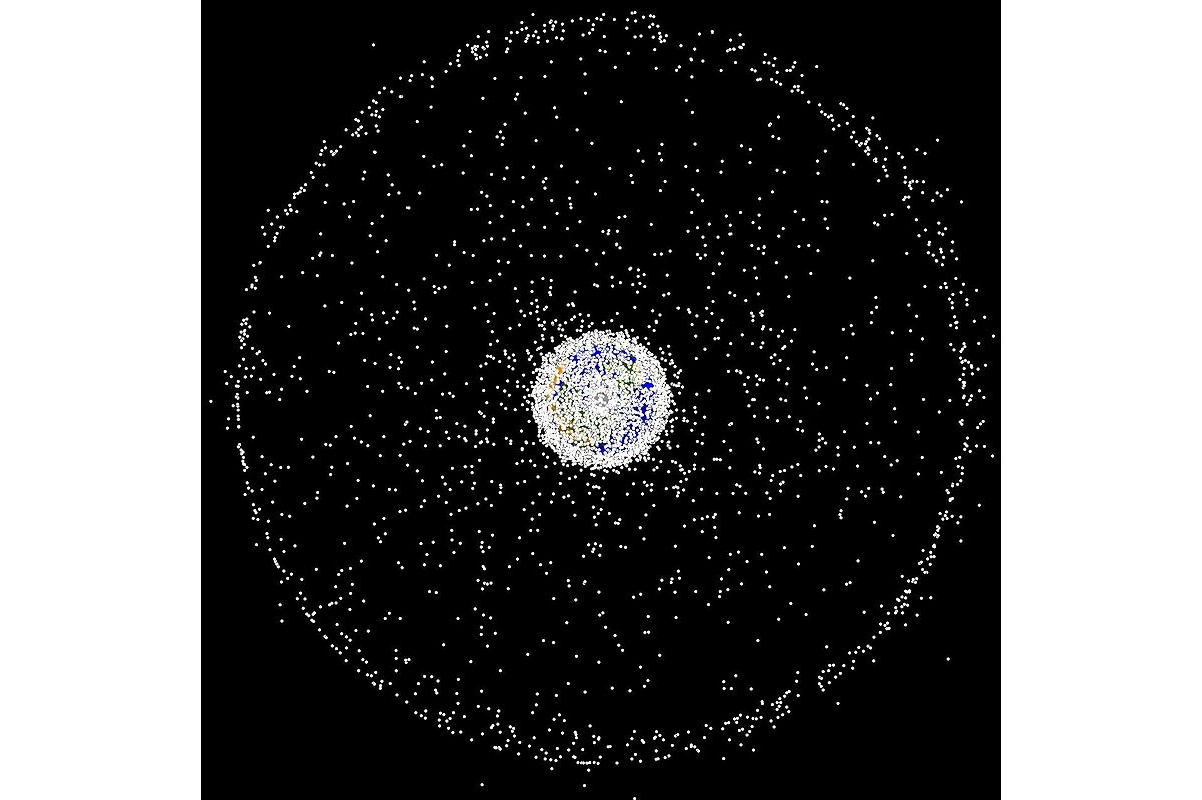

Since the dawn of the space age in the 1950s, there has also been the rapidly growing problem of space debris, which refers to any piece of machinery or debris left by humans in space – ranging from obsolete or failed satellites left in orbit at the end of their missions, to smaller objects such as pieces of satellites which might have fallen off rockets launched into space.

Since the dawn of the space age in the 1950s, there has also been the rapidly growing problem of space debris, which refers to any piece of machinery or debris left by humans in space – ranging from obsolete or failed satellites left in orbit at the end of their missions, to smaller objects such as pieces of satellites which might have fallen off rockets launched into space.

The Natural History Museum reckons that there are around 34,000 pieces of space junk bigger than 10 centimetres in size, and millions of smaller pieces that could nonetheless prove disastrous if they come into contact with either humans or objects.

Several potentially catastrophic incidents (fortunately not involving the loss of any lives) illustrate the seriousness of space debris:

- 23rd April 1958: the 2nd and 3rd stage of the Vanguard missile landed 1,500 miles from the original launch site;

- 24th January 1978: the Soviet Cosmos 954 satellite made an uncontrolled landing over the Northwest Territories of Canada littering hazardous radioactive debris;

- 30th April 1979: fragments of the Skylab space station fell in Western Australia;

- 29 April 2021: China launched its Long March 5B rocket, also known as ‘Changzeng-5’, to deliver the first module of its new space station into orbit. About a week later, the 23-tonne rocket began hurtling back to Earth at 18,000mph, as a consequence of being launched into a slightly higher orbit than normal;

- 9th July 2022: a module from a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft was found on a farm in New South Wales;

Miguel-Ricardo, the recipient of The City Law School’s first ever PhD Scholarship for Black Researchers, is writing his dissertation on the extent to which the private sector can assist spacefaring states to adopt sustainable norms to address the space debris problem.

To properly contextualise the issue, Miguel-Ricardo says space debris belongs to the ‘pacing problem’, first propounded by Larry Downes. The pacing problem arises where “technology changes exponentially, but social, economic and legal systems change incrementally”.

Miguel-Ricardo believes that the secondary lawmaking power or regulatory policies of a government often play a far greater role in determining how to manage the risks associated with using innovative forms of technology in the public sector, than any primary lawmaking function.

There have been several soft law treaties which have sought to regulate the activities of space-faring nations. These include The ‘Rescue Agreement’ 1968; The ‘Liability Convention’ 1972; The ‘Registration Convention’ 1974; and the The ‘Moon Agreement’ 1979. Of these, the opening text of the Registration Convention of 1974 (Space Surveillance & Tracking (SST) calls for an “appropriate registry” and ‘a mandatory system of registering objects launched into outer space, to assist in their identification’.

Miguel-Ricardo’s research so far has also revealed that the European Space Agency (ESA) and the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) trumped the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), by founding a space debris mitigation committee in 1995 – the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC). The IADC created the world’s first ever space debris mitigation guidelines in 2002, the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines. The United Nations General Assembly adopted the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space on 22 December 2007.

The IADC Guidelines have now been revised several times to continue influencing the international community and the ESA eventually agreed to their own European Code of Conduct on Space Debris Mitigation in 2004.

Despite these guidelines being in place, however, Miguel-Ricardo says lawmakers do not have enough information at their disposal about the technological risks they need to regulate before enacting statutes around space debris reduction.

New private and commercial actors in the spacefaring space such as SpaceX, have provided new challenges as well.

He says: “With regard to the modern commercial space ventures entered into by the three major spacefaring nations, this suggests that space agencies and regulators are now inundated with technological data which was previously difficult to accurately process (e.g., the number of debris particles littered in orbit during missions) – without a clear understanding of how to actually remove the junk.”

“There has also been a change in the approaches which major spacefaring nations are taking towards accessing outer space sustainably, whereby they are working with a wider range of actors from the private sector on debris mitigation”

Miguel-Ricardo thinks that “through the contractual adoption of voluntary soft law guidance on debris mitigation and removal, these private sector actors can have a significant influence on the approaches of space agencies towards sustainability in modern commercial space ventures.”

He is persuaded that the private-public partnership (PPP) funding arrangements used in major infrastructure projects in the UK could offer a solution.

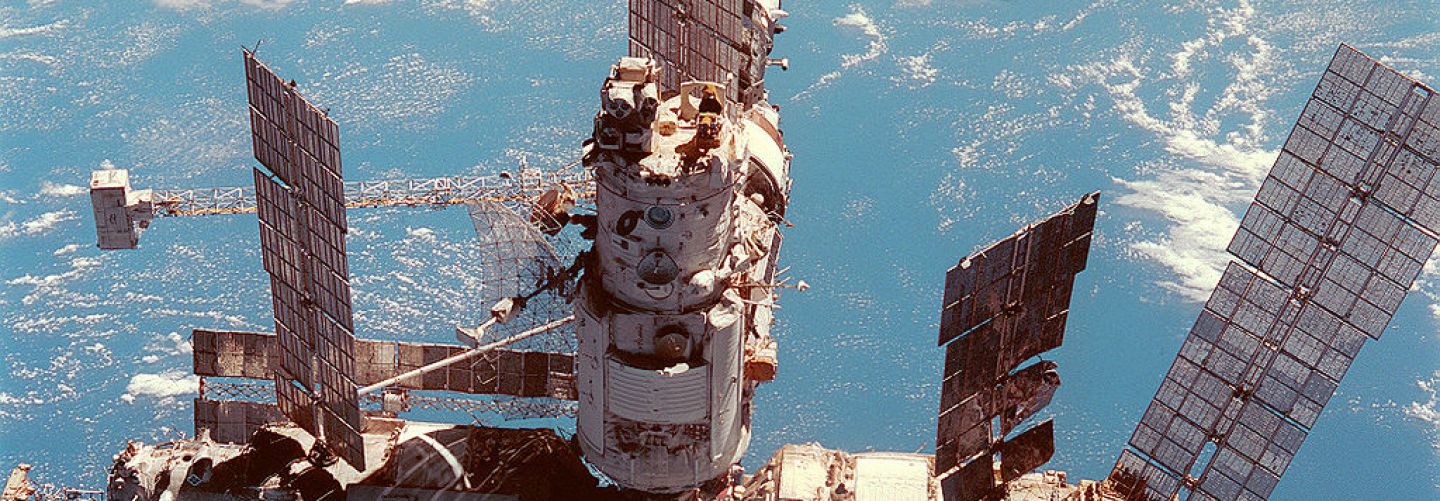

He cites the way that NASA and SpaceX have collaborated to engage in commercial space flights – via SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft– to transport astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) and back more sustainably; and the PPP agreement signed to return NASA astronauts back to the moon on SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft.