Dr Aldo Zammit Borda discusses the role of the Uyghur Tribunal.

By Mr John Stevenson (Senior Communications Officer), Published

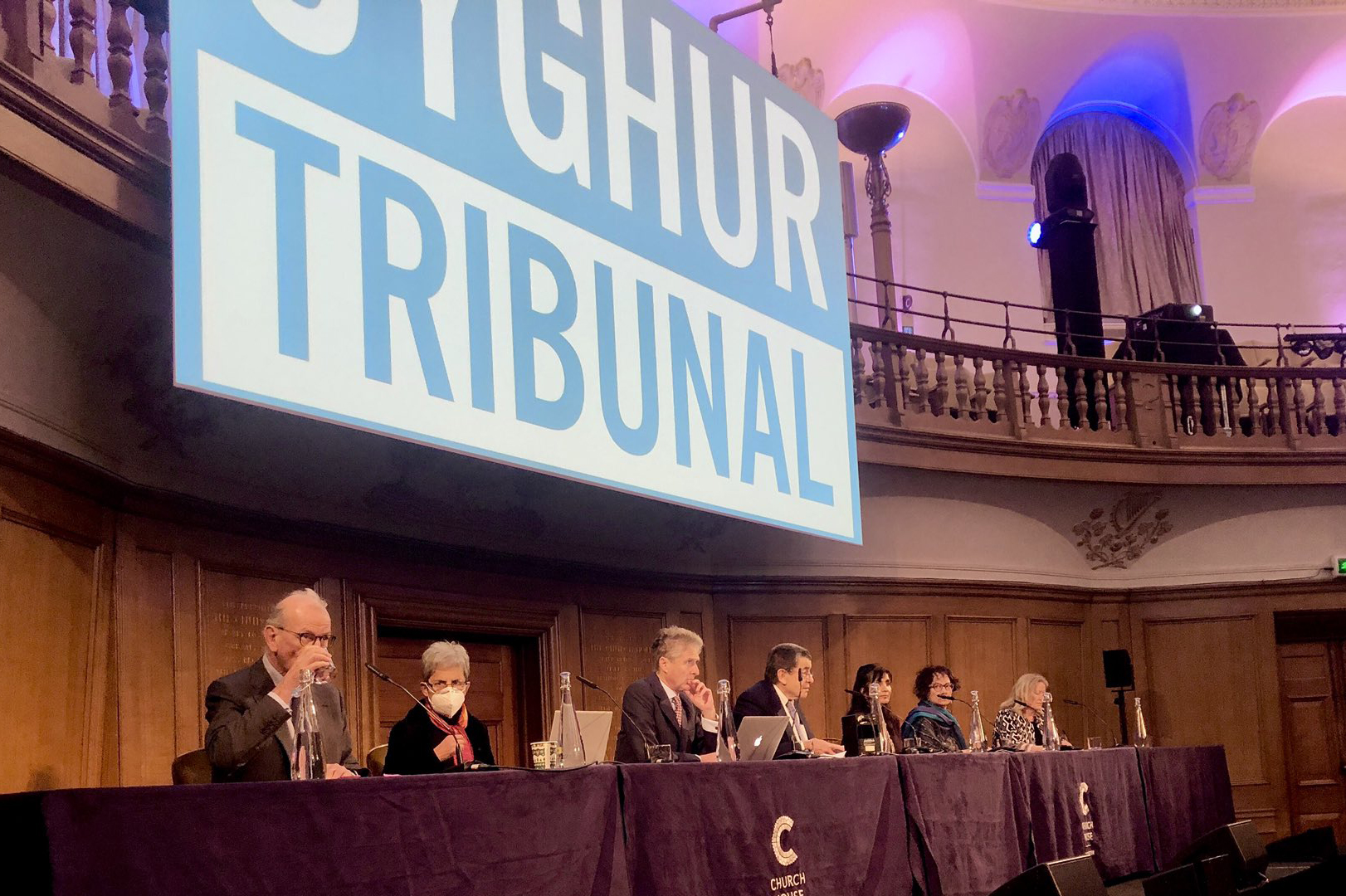

The Uyghur Tribunal (UT), chaired by eminent barrister, Sir Geoffrey Nice, was recently created to consider allegations that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has committed genocide, crimes against humanity and torture against Uyghur, Kazakh and other ethnic minority citizens in the north west region of China known as Xinjiang.

It delivered its judgment, available on its website on 9th December 2021.

Dr Aldo Zammit Borda, Reader in Law at The City Law School, is UT’s Head of Research and Investigation.

City News caught up with him to ask about his varied perspectives on justice for Uyghur, Kazakh and other ethnic minority citizens.

City News: How close is the Uyghur Tribunal to successfully bringing a case against the Chinese state to the International Criminal Court?

Dr Aldo Zammit Borda: The Uyghur Tribunal judgement found that the PRC had committed the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity and torture against the Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang.

It was necessary to establish the UT as an informal tribunal, because the PRC, as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, had the power to close down any avenues for justice within the United Nations system. And, indeed, the PRC used this power in practice. For instance, it blocked the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights from entering China to undertake an independent investigation of allegations of crimes. China was only prepared to grant access to the United Nations High Commissioner if it the investigation was conducted on China’s terms.

It was necessary to establish the UT as an informal tribunal, because the PRC, as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, had the power to close down any avenues for justice within the United Nations system. And, indeed, the PRC used this power in practice. For instance, it blocked the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights from entering China to undertake an independent investigation of allegations of crimes. China was only prepared to grant access to the United Nations High Commissioner if it the investigation was conducted on China’s terms.

As to your question regarding the International Criminal Court (ICC), the PRC is not a member of the Rome Statute of the ICC. For this reason, the ICC does not have direct jurisdiction over the crimes occurring in Xinjiang, China.

In view of these significant limitations of global justice and of the formal routes to justice, without the UT, the PRC would have been able to abuse its victims twice. Firstly, by injuring them and secondly by silencing and preventing them from accessing justice.

The chair of the UT, Sir Geoffrey Nice, held in announcing the UT judgment that “Had any other official body or court, domestic or international, determined or sought to determine these issues the UT would have been unnecessary.” However, because of the status of the PRC in the United Nations, such formal channels for justice were closed.

Having said this, there are currently other attempts, not linked to the UT, to establish jurisdiction over the situation in Xinjiang indirectly. It may be possible, for, instance, for the ICC to exert jurisdiction over Uyghur-linked cases in the territories of States Parties. This is because, in addition to committing crimes against Uyghurs in Xinjiang, there are allegations that the PRC has also pursued Uyghurs residing abroad, some of whom resided in countries that are members of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

CN: To what extent does the recent civil unrest in Kazakhstan bring attention to the work of the Uyghur Tribunal?

AZB: The current unrest in Kazakhstan may be relevant in different ways. One thing that immediately jumps out in the media reports is the labelling of even peaceful protesters as ‘terrorists’ – and the government authorizing lethal force against them. This is a pattern that was witnessed even in Xinjiang. Uyghurs were labelled as being ‘extremists’ merely for having beards or other signs of religiosity. The UT found that the PRC has implemented a comprehensive policy of destruction of physical religious sites, conducted a systematic attack on Uyghur religiosity for the stated purpose of eradicating religious ‘extremism’.

CN: Renowned international law academic Richard Falk says people's tribunals have a 'residual responsibility' to respond to unanswered calls for action in terms of human rights abuses. How would you assess the international reception of the Uyghur Tribunal's work to date?

AZB: As an independent and impartial Tribunal, the sole objective of the UT was to consider the evidence before it and to deliver a judgment on that evidence. It is not an activist institution and therefore any action following the Tribunal would be dependent on others.

And, indeed, immediately after the judgment delivery, a panel of UK parliamentarians held a press conference urging the UK government to consider the judgment findings seriously, particularly when assessing its relations with the PRC. The judgment may also have influenced the approaches of other governments across the world. For instance, it reportedly provided the momentum for the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to bring forward the publication date of her report on the situation in Xinjiang.

And it provided greater legitimacy to countries and institutions, such as the European Union, who have imposed sanctions on China because of the crimes being committed in Xinjiang. Their serious concerns have been vindicated by the findings of the UT.

CN: What challenges did the Tribunal experience in obtaining reports from Uyghur, Kazakh and Turkic Muslim victims and survivors?

AZB: The UT reviewed over 500 fact witness statements – or excerpts and selected 33 witnesses to give live evidence. Amongst these were re-education camp survivors, teachers, and relatives testifying about missing family members and the horrors they suffered. In addition, the UT heard the testimony from 40 experts from across the globe.

Many of the witnesses who testified at the UT did so at considerable personal risk to themselves and their families. However, they were determined to ensure the world learns about the fates of the Uyghurs and other minorities.

CN: It has been over a year since European negotiators concluded a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China. To what extent is growing disquiet in Europe over human rights abuses in China influencing the response of the EU to the plight of Muslim minorities?

AZB: The relationship of different countries and organisations with the PRC is complex and multifaceted. In the case of the EU, under the EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime, the European Union sanctioned several Chinese individuals and entities because of their association with massive human rights abuses in Xinjiang, China. These sanctioned individuals are subject to an asset freeze in the EU. In addition, listed individuals are subject to a travel ban to the EU. Moreover, persons and entities in the EU are prohibited from making funds available, either directly or indirectly, to those listed.

However, the PRC wields increasing economic power and influence and there are those countries, companies and individuals who are more than willing to close their eyes to such massive violations, in order to continue to do business with China, including buying products (many of which are difficult to trace) that may have been connected with or tainted by forced labour of the Uyghurs and other minorities.

I do realize that there are many cases of countries, companies and individuals who have continued to trade and invest with regimes that have committed human rights violations, and that sometimes it is necessary to do so. But in the case of the PRC, we are speaking about the crime of genocide. And following the UT’s finding that the PRC has committed genocide against the Uyghurs, nobody can any longer claim that they did not know.

CN: How has the academic community - international relations and human rights scholars - responded to the work of the Uyghur Tribunal?

AZB: The UT has made available, for the first time and in a single place, a large body of evidence and analysis of crimes occurring in Xinjiang, China. In addition, there were a number of crucial documents belonging to the Chinese state that were leaked directly to the UT. These were made available for the first time, through the efforts of whistle-blowers. Some academics have already begun trawling this evidence for the purpose of enhancing knowledge about these crimes and to identify deeper patterns and associations.

CN: Though China is not a signatory to the Rome Statute establishing the ICC there have been documented cases of forced deportation of Uyghurs from China to Cambodia and Tajikistan who recognise the ICC. To what extent is the ICC still a viable route for prosecution?

AZB: There are various efforts being considered to try to offer further access to justice to Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities for crimes committed against them or their families in Xinjiang. These include, for instance, potential domestic trials relating to the importation of consumer goods connected to or tainted by forced labour. Another effort, at the ICC, relates to the investigation of deportations of Uyghurs from places such as Cambodia (a party of the Rome Statute of the ICC) to China.

All these efforts are independent from the work of the UT. However, they may make use of the evidence and material produced by the UT to seek further justice for Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities.